Cell Phones and Cancer:

Your Genes May Tell the Story

Genetic Susceptibility and RF Radiation Modulate Thyroid Cancer

Last January, a team led by Yawei Zhang of the Yale School of Public Health in New Haven published an epidemiological study on the possible link between thyroid cancer and cell phones. Though some “suggestive” associations were seen among long-term users, none was statistically significant. Still, the results “warrant further investigation,” they advised.

Zhang did follow up, and what she found could well change the way people think about cell phone cancer risks.

She discovered that some people have an innate susceptibility to thyroid cancer when exposed to cell phone radiation. These individuals have small variations in their DNA which affect the functioning of seven different genes.

All seven genes regulate DNA repair.

These new findings will appear in the March 2020 issue of Environmental Research. A typescript copy is available now on the journal’s web site.

“The findings suggest that genetic susceptibilities play an important role in cell phone use and the risk of developing thyroid cancer,” Zhang said in a statement. They “could help to identify subgroups who are potentially at risk.”

When asked how common these genetic variations are in the U.S. population, Zhang told Microwave News that their prevalence varies across different ethnic groups. Given the country’s diverse makeup, she said, it’s difficult to estimate how many people are at higher risk.

Origins of the Study: Risks of Diagnostic Radiation

Zhang has been investigating thyroid cancer for many years —largely because, for decades, it has been increasing at a rate greater than any other cancer. In 2015, she and a number of the same members of her cell phone study team reported what they called a “strong association” between exposure to diagnostic radiation —ionizing radiation— and the risk of thyroid cancer. For instance, those who had CT scans (X-rays) had close to a fourfold increased risk of thyroid cancer. The study was based on data collected in the state of Connecticut in 2010-2011 and included 462 cases and 498 controls.

A couple of years later they extended the study with a genetic analysis of many of the same cases and controls. This was possible because all the participants had provided blood samples. Zhang focused on those genes known to be involved in DNA repair.

Zhang found that variations in short sequences in those genes —called SNPs, short for single-nucleotide polymorphisms— are associated with the risk of thyroid cancer in general and, further, that specific variations are associated with an elevated risk following exposure to diagnostic radiation.

“Our study provides novel evidence to suggest a significant interaction between germline mutations in DNA repair genes and ionizing radiation in the pathogenesis of thyroid cancer,” Zhang concluded.

Cell Phone Study

The team then turned to cell phones. Here a traditional epidemiological study showed weak links among long-term users, but significant associations became apparent when the analysis was extended to include SNPs within repair genes. (The second cell phone study covered 440 cases and 465 controls.)

Yale’s Yawei Zhang, the principal investigator

Those who had the variant DNA sequences —usually those with the less common SNPs— had up to a fivefold increased risk of thyroid cancer. Zhang identified ten variant SNPs in seven different DNA repair genes.

Zhang saw associations between higher risks of thyroid cancer and a number of different measures of cell phone use, including the number of calls per day, hours of use and years of use. In many cases, significant trends were found: that is, more use was associated with a higher risk.

As in most retrospective epidemiological studies, there is always the chance that people may misremember their past habits and thereby confound the results —this is known as recall bias. But Zhang discounts this possibility, explaining that “If the increased risks had been due to bias or chance, they should have been observed in the common SNP group as well.”

Zhang and colleagues conclude: “Our results suggest that genetic susceptibilities modify the associations between cell phone use and the risk of thyroid cancer.”

Smartphone Antenna Is Close to the Thyroid

Because the questionnaires were completed about a decade ago for the first diagnostic radiation study, the new cell phone results might not apply to smartphones (e.g. iPhones), which were just coming on the market at the time.

Zhang points out that because the RF antenna on smartphones is located on the bottom of the phone, it is close to the thyroid, entailing more RF exposure than from earlier generations of cell phones. On the other hand, Zhang adds, people are texting more and speaking on the phone less, which would lead to lower thyroid exposures.

Comparing Risks from Ionizing and Non-Ionizing Radiation

Asked to compare the risks from diagnostic radiation to those from cell phones, Zhang replied:

“I expect that diagnostic radiation risks are higher than cell phone risks. Diagnostic radiation is ionizing radiation while cell phone radiation is non-ionizing radiation. However, patterns of exposure are very different, high dose with very short-term exposure vs. low dose with long-term exposure.”

In addition to being a professor in the Department of Environmental Health Sciences at the Yale School of Public Health, Zhang has an appointment in the Department of Surgery at the Yale medical school and serves as the co-assistant director of global oncology at the Yale Cancer Center. She received her medical degree at the Western China University of Medical Sciences in Chengdu. A number of members of her thyroid research team are based in Beijing.

A coauthor on all four radiation papers is Robert Udelsman, one of the most illustrious surgeons in the country. He is the former chairman of the Department of Surgery at Yale medical school, as well as the Surgeon-in-Chief at Yale-New Haven Hospital. Before joining Yale in 2001, he was a professor of oncology and surgery at Johns Hopkins medical school, where, in 1999, he operated on Tipper Gore, then the Second Lady of the U.S., to remove a growth on her thyroid.

Thyroid Cancer Trends in the U.S.

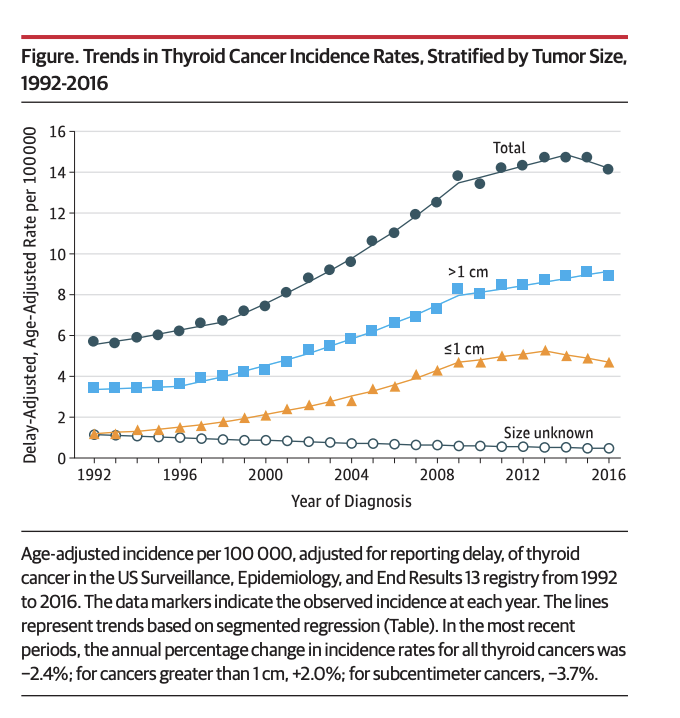

A recent letter in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) reported that after the incidence of thyroid cancer tripled in the U.S. between 1974 and 2013, it appears to have “reached a plateau and possibly started to decline.” As seen in the graph below, small thyroid tumors (those whose size is 1 cm or less) have indeed dipped in recent years, but those larger than 1 cm have not.

Source: JAMA, December 24-31, 2019

Source: JAMA, December 24-31, 2019

When asked to comment about this finding, Zhang said, “As indicated by the authors, the decline of subcentimeter tumors is reflected in changing clinical practice guidelines including recommendations against screening for thyroid cancer by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force in 2017.”

“We speculate that a true increase in thyroid cancer incidence still remains but at a slower pace,” Zhang said. “It is difficult to tell how much of the increase is attributable to cell phone use,” she added.

The Bottom Line

Zhang and her team urge follow-up research. “Given the public health importance, we call for more studies to continue the investigation on the interaction between cell phone use and genetic variants,” they wrote.

“I would love to pursue this line of investigation if we could secure funding,” Zhang told me. “Cell phone use and health has significant public health implications. Identifying susceptible population and understanding exposure to RF radiation from different patterns of cell phone use would be the priority of research in this area.”

_________________________

A Final Note

Over a decade ago, researchers in Shanghai reported that children with variant SNPs in their DNA repair genes were more likely to develop leukemia if they lived close to power lines. (More here.)

The work was never followed up.