Paul Brodeur

The Original Microwave Pioneer

Setting the Record Straight

A Personal Tribute

In the summer of 2012, Paul Brodeur sent me an email that began, “Don’t forget that when I croak, you’re supposed to give some credit to me as the original microwave pioneer.” I came across it in my files after learning that Brodeur had died on August 2nd at the age of 92. It was among his many letters, notes and clippings I had stashed away over the last 50 years.

First Meeting

The story begins on a rainy fall afternoon in 1977 at the New York office of the Natural Resources Defense Council, a public-interest environmental law firm, where I was working at the time. Brodeur, then a star investigative reporter at The New Yorker, came by with copies of his new book, The Zapping of America, an exposé on the dangers of microwave radiation and how they were being covered up. The previous December, the magazine had run two long articles by Brodeur which caused a national sensation and drew attention to the otherwise obscure world of electromagnetic health.

Brodeur’s mission that day was to talk NRDC attorneys into tackling the microwave problem. With him was Dr. Milton Zaret, a noted New York ophthalmologist, who had been a consultant for the CIA and was now blowing the whistle, alleging that microwave radiation could cause cataracts at levels well below existing exposure limits.

I shouldn’t have been at NRDC that day. I was supposed to be finishing my doctoral thesis, but I much preferred the action at the office to sitting at home alone staring at my typewriter. That was the first time I met Brodeur in person, though I was already well acquainted with his work. I had read the two microwave articles and, years earlier, his landmark 1968 New Yorker article on the hazards of asbestos, “The Magic Mineral.” After Brodeur, asbestos would never be seen the same way again.

The Magic Mineral in the October 12, 1968, New Yorker

The Magic Mineral in the October 12, 1968, New Yorker

By the time Brodeur and Zaret had finished their pitch at NRDC, I was hooked. When the meeting ended, I grabbed a copy of Zapping, and I was soon taking time from my assigned responsibilities —dogging EPA on toxic chemical regulations— to work on microwaves. An NRDC lawyer and I took on OSHA for its lax—unenforceable— exposure limit and the U.S. Air Force for its incomplete assessment of its massive radar on Cape Cod, known as PAVE PAWS. In 1980, after I completed my PhD in environmental policy, I left NRDC and launched Microwave News—with help and encouragement from Brodeur.

Nine years later, Brodeur published the second of his three books on electromagnetic radiation and health: Currents of Death. This too had first been serialized in the New Yorker. I hated the title, yet I was more than a little pleased that Brodeur, who had made good use of my reporting in Microwave News, gave me top billing in his acknowledgements on the opening page. The book would be more controversial than I ever imagined.

With that background, I will honor Brodeur’s charge and lay out his role in microwave and power line history. Let there be no doubt, he was the original microwave pioneer.

Alarmist and Conspiratorial?

I begin at the end of the story. In a lengthy and generous obituary, the Washington Post praised Brodeur’s work on asbestos —the reporter called The Magic Mineral a “journalistic tour de force.” But he was far less complimentary about Brodeur’s writings on radiation:

“While Mr. Brodeur was widely hailed for his reporting on asbestos and the ozone layer, some scientists said he was unnecessarily alarmist, even conspiratorial, in raising concern about potential health effects caused by power lines, cellphones and other household devices.”

The New York Times obit also hailed The Magic Mineral, placing it in the same league as Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, which itself had been serialized in the New Yorker. The obit didn’t get to microwaves and power lines until the 22nd of 33 paragraphs. It dismissed Brodeur’s work with a slap from William Broad, a veteran Times science writer who has derided such health risks —and Brodeur in particular— for decades.

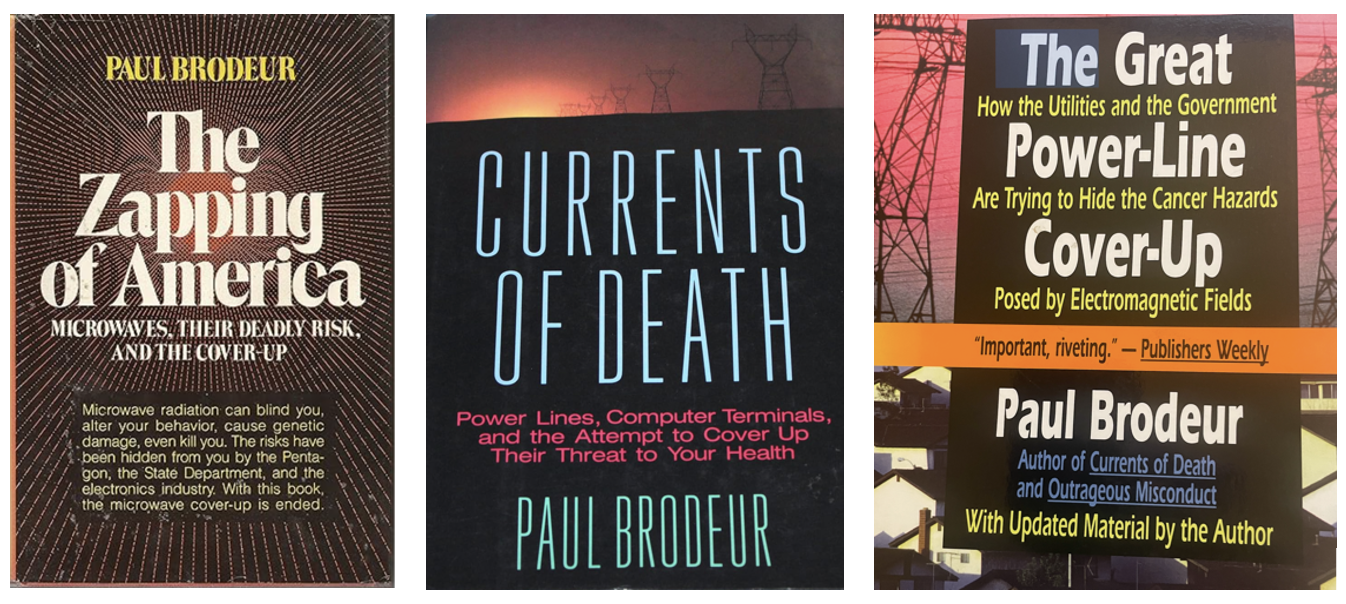

Brodeur’s Three Books on Electromagnetic Radiation

Brodeur’s Three Books on Electromagnetic Radiation

The tables had turned. Brodeur, once a public health hero, was now an alarmist. What happened? How could someone who everyone agreed got it so right on asbestos, now be vilified for getting it so wrong on microwaves and power lines?

It’s a long story. The short version is that Brodeur got it right:

• Microwave radiation and power-frequency electromagnetic fields can lead to profound biological changes. The microwave-cancer connection, far from being fanciful, seems more than likely today.

• Beyond any reasonable doubt, there was, and continues to be, a cover-up. Powerful forces —initially the military-industrial complex, and now society as a whole— have insisted that the radiation cannot harm us except through heating. Further research has been consistently delayed and suppressed.

Fact-Checked and Re-Checked

Brodeur had a rare privilege in journalism: The New Yorker offered him the time and resources to dig into a story. His writing is rich with specifics — details from face-to-face interviews, scientific papers and government reports. He then organized them into clear and compelling stories —most often, with a moral imperative to right the wrongs.

Science takes center stage in Brodeur’s exposés, with medical experts showing the way. In the Magic Mineral, Dr. Irving Selikoff, an occupational physician at the Mount Sinai medical school in New York City, tracks down excess disease among asbestos workers at a New Jersey insulation factory. In Zapping, Zaret, a sought-after ophthalmologist at NYU’s medical school, finds himself operating on an unusual number of young cataract patients and infers that workers exposed to microwaves develop them at levels well below the exposure limits. And in Currents, Nancy Wertheimer, a Harvard-trained epidemiologist, and her colleague Ed Leeper make the unlikely connection between power lines in Denver and childhood leukemia.

Brodeur on his 90th Birthday (Family Photo)

Brodeur on his 90th Birthday (Family Photo)

Brodeur relied on specialists to help him cut through the technical details. For Zapping, he turned to Leo Birenbaum, a professor at Brooklyn Polytechnic. Birenbaum, a talented engineer, was well-informed and well-connected. He had a foot in both camps. For years he was the secretary of the U.S. Navy subcommittee that wrote the microwave exposure standard. He attended the meetings and prepared the minutes for the record. Birenbaum was also a friend and colleague of Zaret’s.

When Brodeur had finished his last draft, there was a final backstop —the legendary New Yorker fact-checking department. (Even the poetry in the magazine was said to be looked over.) I saw the process in action on the 1989 three-parter which became Currents. Presenting backup from reliable sources was non-negotiable.

The Fallout from Zapping

The Zapping of America was published in 1977, less than a year after Brodeur’s two microwave articles appeared in the New Yorker. A blurb on the jacket cover summed up his message in two sentences:

“Microwave radiation can blind you, alter your behavior, cause genetic damage, even kill you. The risks have been hidden from you by the Pentagon, the State Department and the electronics industry.”

Elting Morison, the eminent American historian, gave it a favorable review in the New York Times. He understood what Brodeur was doing. “The book is an illustration, laid out in black and white to capture the attention,” he wrote. “The purpose of Zapping of America is to arouse citizens to the task of acting effectively in the general interest and welfare.” In that, Brodeur surely succeeded.

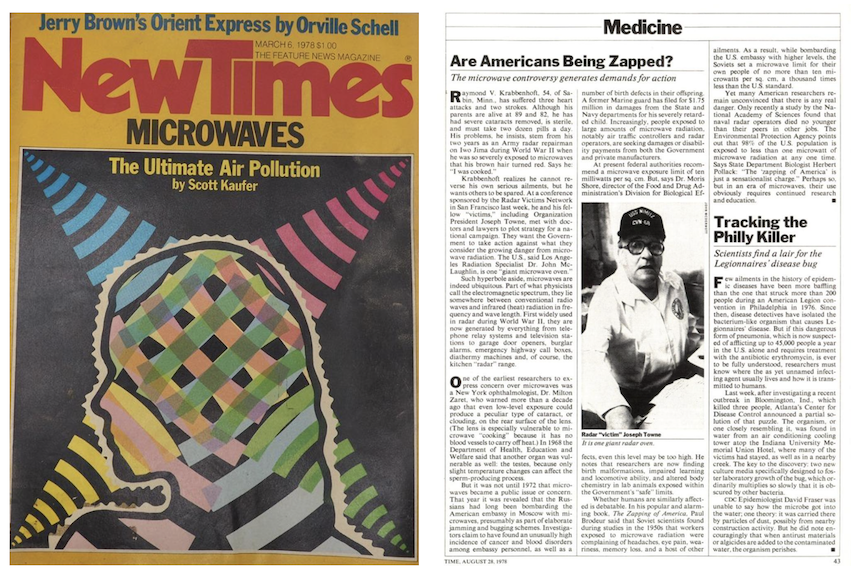

New Times and Time magazines in 1978

New Times and Time magazines in 1978

Many magazines picked up the story. IEEE Spectrum, New Scientist, New Times, New York and People, among many others, ran major follow-ups. Time magazine did too, under the headline: “Are Americans Being Zapped? The Microwave Controversy Generates Demands for Action.” It featured the Radar Victims Network, a group of injured military and civilian technicians. Before Brodeur, only Jack Anderson, the nationally syndicated columnist, had taken up their case for compensation.

Some countered that Brodeur had overstated the microwave health risks. But within a couple of years, there was general agreement that exposure limits were too lax.

In 1982, the U.S. exposure standard was lowered by a factor of ten. A decade later it was reduced by another five-to-tenfold. Before Brodeur, the standard had not been changed in 30 years —not since it had first been proposed in 1953 at a meeting at the Naval Medical Research Institute outside Washington. By the early 1990s, the standard had become 50-to-100-times more protective.

The Cover-Up Never Stopped

The exposure limits may have been tightened, but the cover-up continued. Research was suppressed —allowing uncertainties to fester. All effects other than overheating were deemed inconclusive and their existence denied.

The cover-up had been going on for a long time, as Brodeur had reported. In 1968, for instance, Colonel Alvin Burner, the Chief of Radiobiology at Brooks Air Force Base in San Antonio, drafted a plan to fill, as he put it, “the tremendous gaps in our knowledge.” That initiative was soon scuttled, and Burner transferred to the Pentagon, where he had no further say on microwave research. Jack Anderson, at the time America’s leading muckraker, recounted what had happened in a 1973 column headlined, “Air Force Ignores Microwave Peril.”

About a year later, Anderson broke the story of the Soviets beaming microwaves at the U.S. embassy in Moscow and the top-secret military investigation —Project Pandora— to determine whether it might be harming the embassy staff. (The State Department had not told anyone about the microwaves for more than 20 years.) Throughout the 1970s, Anderson devoted numerous columns to microwave injuries, especially among radar workers. It was one of these that caught the attention of William Shawn, the editor of the New Yorker. Shawn passed it on to Brodeur suggesting that he might investigate whether there was a story for the magazine. The tip led to Zapping.

Another example of the cover-up in action: In 1979, John Thomas, a Navy scientist, published a groundbreaking paper in Science magazine, one of the world’s top journals. It showed how low-intensity microwaves (a level ten times lower than the then-current exposure limit) could act synergistically with Librium, a tranquilizer used by millions of Americans. (It’s in the same family of drugs as Valium and Xanax.) The Navy closed the project down. Like Burner, Thomas was sent packing —transferred to do cold-weather research (I’m not joking!).

When an Air Force animal study prompted by Zapping showed higher rates of cancer, the results were kept under wraps for years. After being presented at a scientific meeting in 1984 and making national news, they did not appear in a journal for another eight years. The observed increase in tumors, which the USAF’s own pathologist called “provocative,” went unmentioned in the summary statement when the paper was finally published in 1992.

Despite the link to cancer, the microwave research group at the Environmental Protection Agency, one of the largest and most productive in the world, was disbanded. The agency was forced to shelve its plan to establish a national microwave exposure standard. No such limit has ever been set.

Perhaps the best example of the effectiveness of the cover-up is what happened with two important effects: microwave hearing and increased leakage through the blood-brain barrier. Both were first demonstrated in the 1960s/70s by Allan Frey, an independent and iconoclastic scientist. Both are discussed in Zapping. Understanding them might help explain reports of everything from headaches to brain tumors. The effects remain unresolved —and are as controversial today as they were 50 years ago.

Frey, now 89, discovered that people could hear pulsed microwaves as buzzing, clicking, hissing or knocking sounds. It’s often called the “Frey Effect” and has been much in the news over the last few years in the context of Havana Syndrome.

Shift to Power-Line Frequencies

After Zapping, Brodeur returned to asbestos, with a four-part series in the New Yorker on its impact on workers. It won a National Magazine Award. The series was later republished in 1985 as Outrageous Misconduct: The Asbestos Industry on Trial. The book received a favorable reception. “Even a confirmed skeptic will find astonishing Brodeur’s account of the asbestos industry’s avaricious inhumanity towards millions of workers and members of the public,” said the Harvard Law Review.

Brodeur then circled back to electromagnetics. This investigation, also serialized in the New Yorker, was published as Currents of Death in 1989, and was followed, in 1993, by The Great Power-Line Cover-Up. That’s when the big trouble started.

In contrast to Zapping, which caught most by surprise, Brodeur’s writings on power lines arrived amid already growing public concern over EMFs. The outline of the story in Currents is similar to that in Zapping: growing evidence of cancer and a cover-up. Yet this latter clarion call received a far more negative reception.

In 1989, when the New Yorker power-line articles and Currents came out, a decade had passed since Wertheimer and Leeper had uncovered the link to childhood leukemia, and a few years since it had been replicated.

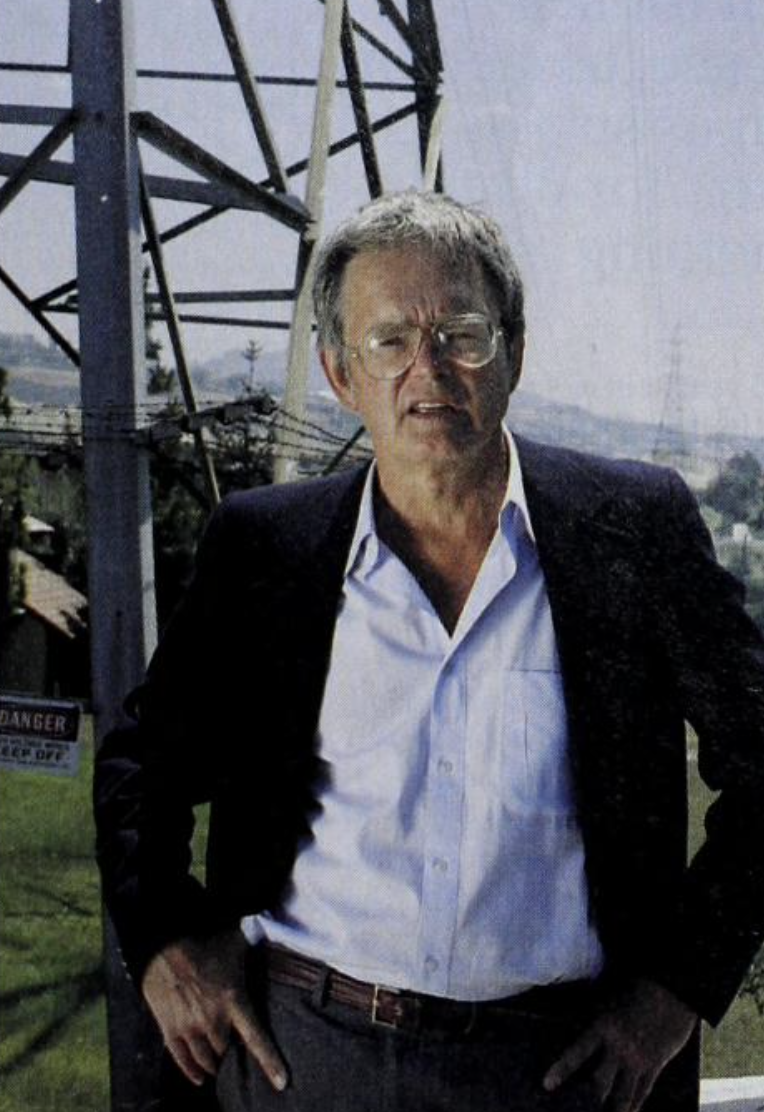

Brodeur in Newsweek, July 10, 1989, issue (Photo: James Aronovsky)

Brodeur in Newsweek, July 10, 1989, issue (Photo: James Aronovsky)

Indeed, at exactly the same time the New Yorker series was hitting the newsstands, the Congressional Office of Technology Assessment (OTA) issued a report on the biological effects of power-line EMFs, prepared by a group at Carnegie Mellon University. Here was the key conclusion:

“[T]here is now a very large volume of scientific findings based on experiments at the cellular level and from studies with animals and people which clearly establish that low-frequency magnetic fields can interact with, and produce changes in, biological systems.”

As for cancer, the report advised:

“[T]he possibility of cancer promotion appear[s] most worthy of concern with respect to public health effects.”

The message was in sync with Brodeur’s, albeit with much milder language: Power-line effects are real, and the cancer risk needs attention.

Less than a year after Currents, the cancer link got a big boost. The U.S. EPA prepared a report concluding that EMFs were “probable human carcinogens.” It leaked out and made international headlines. (More about that in a minute.)

The epidemiological evidence of a cancer link kept piling up. It could not be dismissed. In 2001, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) —widely considered the gold standard for assessing cancer agents— weighed in. An IARC panel of 20 experts concluded —unanimously— that Nancy Wertheimer had been right all along: EMFs are possible human carcinogens.

Cover-Up from the Get-Go

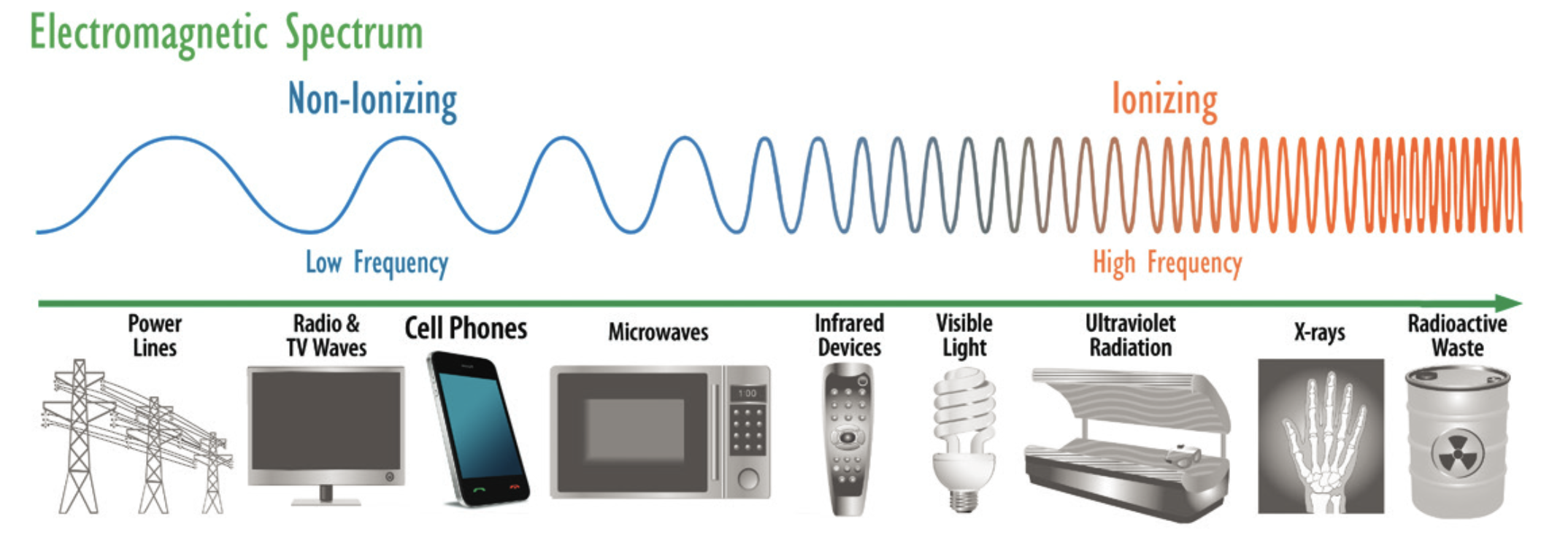

EMFs and microwaves occupy different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum. EMFs are at the low end; microwaves have frequencies millions of times higher. But their health effects are studied by the same community of scientists. Here again, the military was in control, and cover-ups were routine. The Air Force was dominant on microwaves, while the U.S. Navy ran the show at the extremely low frequencies, known as ELF.

Source: NTP Fact Sheet

The Navy’s interest was rooted in a plan, hatched in the 1950s, to use ELF signals to send messages to submarines running deep thousands of miles away. The project called for building the world’s largest antenna: It would cover more than 20,000 square miles —a third of the entire state of Wisconsin. Project ELF, as it was sometimes called, rankled the fiercely independent residents of the North Woods. One local activist feared the project would cause “a new kind pollution, bordering on the realm of science fiction.”

The project was kept secret until the late 1960s. As details trickled out, early studies pointed to possible health and ecological effects. The Navy convened a special panel to evaluate what was known and what more was needed. Committee members made a list of research priorities —many were deemed “Urgent and Absolutely Necessary.” The Navy immediately buried the panel’s report and kept it hidden from Congress and the public for two years.

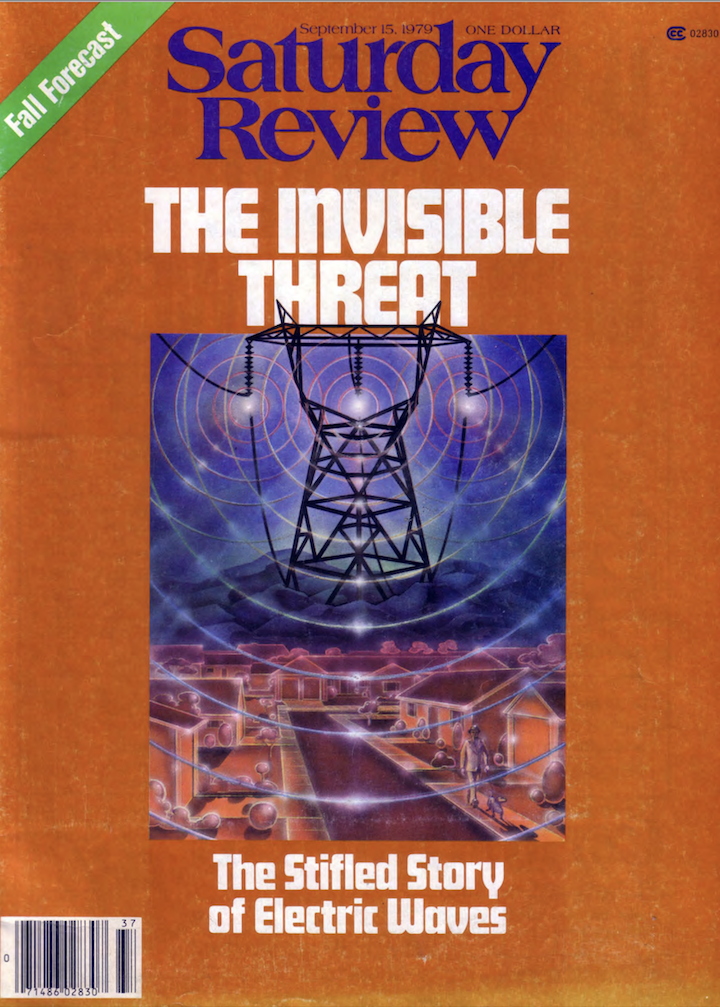

After Zapping, but still ten years before Currents, the Saturday Review, a prestigious, large-circulation magazine, made the case that there was a cover-up at the lower power-frequencies too. “The Invisible Threat: The Stifled Story of Electric Waves” came out in the fall of 1979, at about the same time as the Wertheimer-Leeper leukemia study appeared in the American Journal of Epidemiology.

Saturday Review, September 15, 1979

Saturday Review, September 15, 1979

The Navy kept a tight grip on the science that might affect its submarine project. It helped launch the Bioelectromagnetics Society to foster research, with its people installed at the top, including the editor-in-chief of both its journal, Bioelectromagnetics, and its newsletter. The Navy also ran the committee that set electromagnetic health standards, until the 1980s when the IEEE, an electrical engineering society, took it over.

In the 1980s, the Electric Power Research Institute —it now calls itself simply EPRI— got more involved. It shared the Navy’s concerns and objectives. The Navy wanted an antenna; electrical utilities, EPRI’s members, wanted power lines.

Each dealt with the Wertheimer-Leeper bombshell in its own way. The Navy ignored it while EPRI discredited it. EPRI would take close to eight years to commission a replication, and that was only after the cancer link had been repeated and confirmed by David Savitz with money from New York State.

The cover-up never stopped. It has already outlived Brodeur. Ten days after he died, the journal Environmental Research posted a paper rehashing, for the umpteenth time, the same old industry arguments on the role of EMFs in childhood leukemia. It had been paid for by EPRI.

The boundaries of knowledge have not moved forward. After the IARC classification as a possible carcinogen in 2001, most EMF health research stopped cold.

One of the longest and harshest reviews of Currents was in Scientific American by Granger Morgan, a professor at Carnegie Mellon and a coauthor of the OTA report. It went on for six pages and dismissed any suggestion of a cover-up. Morgan called Brodeur’s accusations the “ravings from an extremist fringe.”

Morgan made a point of defending EPRI. One of Brodeur’s chapters on EPRI is titled “Obfuscation.” Morgan characterized EPRI as a positive force and gave it credit for doing a “remarkably good job.”

The media critic at the Village Voice, the former NYC weekly, itself a home for muckrakers, called Morgan out for swooning over EPRI without mentioning that, a little more than a year earlier, he and Carnegie Mellon had received more than $300,000 from EPRI to study EMFs (that’s about $750,000 today).

Some others found Brodeur’s claims of a cover-up a hard sell. A Newsweek science correspondent called them “overblown.” He did not dismiss the problem. “We’re not quite sure what we’re up against and we urgently need to find out,” he wrote. But as for the cover-up:

“[Brodeur] does document remarkable instances of military and corporate cynicism, of narrow mindedness among scientists and of complacency among public health officials and the press. But the implications of a cover-up seem overblown.”

With all that skullduggery, why did he doubt a cover-up?

“[Brodeur] makes much of the fact that throughout the 1970s and early 80s, most scientists held to the mistaken belief that [power line] fields can’t affect an organism because they don’t cook tissue as microwaves do. Research at the level of the cell has since shown that the conventional wisdom was wrong and responsible scientists now admit as much.”

That was in 1989. Today, some 35 years later, that allegedly debunked “conventional wisdom” continues to hold sway.

Physicists Doing Biology

The obituary writer at the Washington Post did not name the scientists who accused Brodeur of being a scaremonger. He was likely referring to any of a number of physicists at Yale University who objected to the idea that power-line EMFs could lead to cancer or any other ill effects.

The leader of the Yale pack was Robert Adair, who held a prestigious Sterling Professorship. Adair made his name in particle physics. Then, on turning emeritus, he segued into electromagnetic biology, a field in which he had no apparent experience. His wife, Eleanor, on the other hand, was an expert on microwave heating. She spent five years as a senior scientist at the U.S. Air Force’s microwave lab in San Antonio.

The Adairs were leaders of the heating-only camp —anything else, they argued, would violate the laws of physics. Non-thermal effects were deemed scientifically impossible. Today, more than 30 years later, the same strictures apply; only the flag bearers have changed.

Robert Adair ridiculed the idea that power-frequency fields could be linked to cancer. “There’s probably nothing on Earth, or in the universe, that we understand as well as electromagnetic fields, and the interaction of electromagnetic fields with matter, including biological matter,” he claimed in a Frontline documentary. Power-line fields are millions of times too weak to affect DNA, according to Adair.

“Such weak fields cannot be expected to affect biology or, therefore, the health of the population,” Adair wrote in a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (he was a member). There were many other Adair papers, all reaching similar conclusions.

Adair’s influence was greatly enhanced by his good friend Allan Bromley. He too was a physicist with a Sterling professorship at Yale. When Currents was published, Bromley was the science advisor to President George H.W. Bush. Bromley became the ultimate arbiter within the federal government of what EMFs could and could not do. No surprise, he sided with Adair.

When the EPA report concluding EMFs were probable carcinogens became public in 1990, Bromley intervened and the report was put on hold. He probably got another nudge from the CEO of EPRI, who was making the rounds in Washington, visiting both the White House and the National Academy of Sciences. A new panel was quickly assembled to offer an opposite opinion. When the EPA finally released the report, the probable classification had been removed.

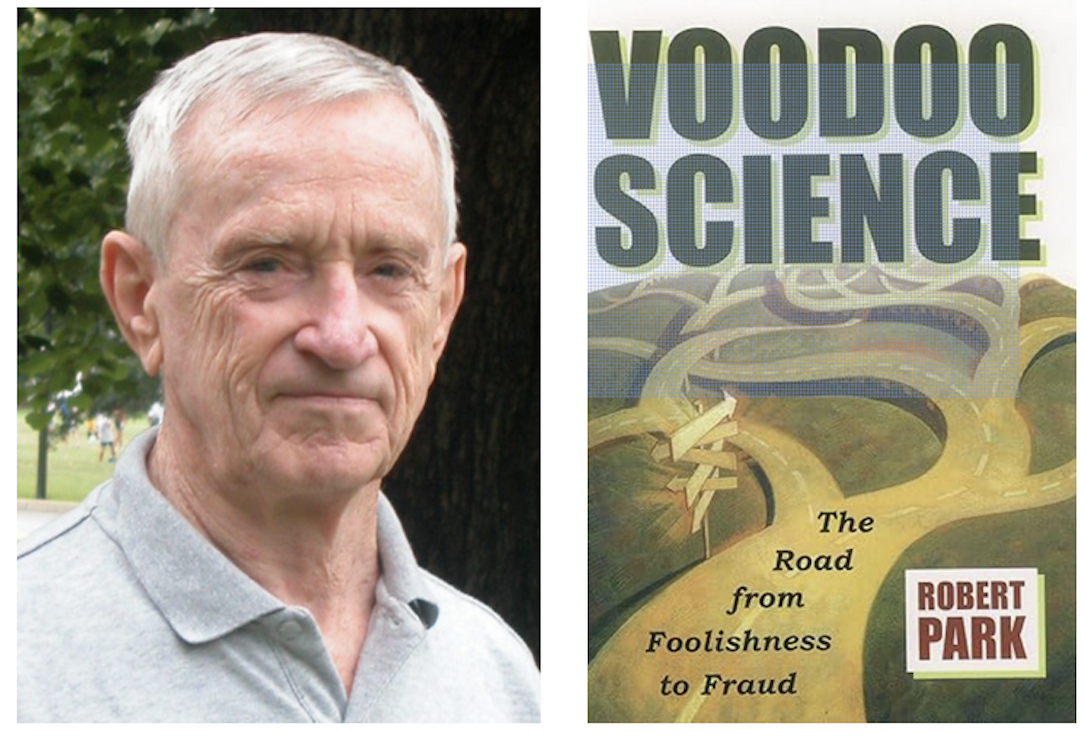

Robert Park: It’s Impossible

The Yale physicists were rich in Ivy prestige and insider influence, but the scientist with the loudest megaphone was Robert Park, the American Physical Society’s lobbyist in Washington. Park was a skillful writer, best known for his weekly newsletter, “What’s New,” where he cultivated a reputation as the nation’s debunker-in-chief. The New Scientist said he was waging “war against bad science.” Park lampooned claims about UFOs, perpetual motion, cold fusion —but, most of all, EMF and microwave health effects.

Over the years, by Park’s own count, What’s New criticized media coverage of cell phones and cancer in 76 columns. There were many others too. It’s more attention than Park devoted to any other issue, such as climate change, atomic energy or nuclear weapons.

When a National Academy of Sciences committee threw cold water on the power line/childhood leukemia link in 1996, Park did a victory lap in the New York Times. His op-ed, “Power Line Paranoia,” crowed that the controversy “has finally been put to rest.” He blamed Brodeur for dramatizing unsubstantiated health hazards and spinning imaginary conspiracy theories.

Brodeur was Park’s favorite target, and his attacks grew more and more shrill. By the new millennium, Park was calling Brodeur a “professional fear-monger” who was fueling “full-scale public paranoia.” At the time, Brodeur had not written about EMFs or microwaves for close to a decade.

Park had become the anti-Brodeur. He wrote and promoted his own book, Voodoo Science, in which Brodeur was a central villain. In a chapter titled “Currents of Fear,” he remarked that the chances of power-line EMFs causing cancer are similar to those of seeing a “stegosaurus running down Fifth Avenue.”

Robert Park and his Voodoo Book

Robert Park and his Voodoo Book

Park won the blessing of the larger scientific community. In 2001, the Journal of the National Cancer Institute (JNCI) invited him to comment on a new paper which purported to put the cell-phone-cancer issue to rest —Park said it was “beautifully designed” (it didn’t and it wasn’t). Though ostensibly about cell phones, his commentary focused on power lines. He once again berated Brodeur. This time it was for spinning “scare stories.”

As with the Adairs, Park’s central argument against a cancer connection was that it’s impossible. Over and over, he repeated the same mantra: Neither EMFs nor microwaves can cause cancer because they don’t have the energy to break a chemical bond. Brodeur had to be wrong, Park claimed, because his science would violate the laws of physics.

It’s true that microwaves cannot break DNA. But, as has been shown innumerable times in the lab, they can affect DNA and the way genes are expressed. Simply put: Park was right about not breaking chemical bonds, but this does not answer the question, Do they present a cancer risk?

No one pointed out the irony that Park, the defender of good science, was using concepts from a high-school chemistry class to shed light on cutting-edge biophysics. Few cared. Business applauded his message, as did the government. Park was offering good news: There was now one less thing to worry about. Park was eliminating a threat which, if believed, might cost billions to remedy.

Reporters Turn Against Brodeur

A major change occurred between the publication of Zapping and Currents: A number of reporters turned against Brodeur. Maybe they were listening to the physicists.

They included Jon Palfreman, whose “Currents of Fear” was broadcast on Public Television’s Frontline, and Gary Taubes, whose “Fields of Fear” was published in the Atlantic —but no one was more savage than William Broad at the New York Times. In a short review of Currents, Broad compared Brodeur to a “person asserting the earthly presence of space aliens.”

William Broad, Gary Taubes and Jon Palfreman (left to right)

William Broad, Gary Taubes and Jon Palfreman (left to right)

Over the years, Broad found many ways to ridicule the EMF–cancer risk. Sometimes he just conjured up a reason to go feral. In 1999, for instance, the Times ran one of his stories on the front page, above the fold, with the headline, “Data Tying Cancer to Electric Power Found False.” Broad wrote about a Berkeley EMF scientist who had been reprimanded for doctoring three graphs —no one claimed that he had altered the actual data. Broad turned it into a cause célèbre that somehow absolved EMFs of any cancer risk. The experiment was nothing special: a minor addition to some decades-old work on the flow of cellular calcium. Any connection to cancer was at best remote. Broad cited Park to tarnish all EMF research. The scientist’s “deception was probably typical for the field,” Park declared.

“The growing consensus among researchers seems to be that electric power is safe,” Broad assured readers. Two years later, the IARC panel unanimously labeled EMFs as a possible carcinogen.

An “Almost Infinitesimal” Risk

Brodeur’s critics have argued that he overstated the possible risks. Any health effects, they argued, would be trivial. Here’s Taubes in the Atlantic on power lines:

What makes Brodeur’s conspiratorial interpretation all the harder to understand is the level of alarm raised compared with the maximum possible level of the threat. Scientists on both sides of the issue say that they are dealing at the very most with rare diseases and an increased risk that is almost infinitesimal —especially compared with all the other risks of everyday life, from driving and smoking to choice of diet.

Maybe, maybe not.

Childhood leukemia is (thankfully) a rare disease, affecting only about 1 in 10,000 children. But if EMFs are sometimes to blame, we should ask, ‘What else may be going on?’ No one thought that living next to power lines might lead to cancer— until Nancy Wertheimer did the work and changed the conversation.

In 1982, three years after Wertheimer’s study appeared in print, Samuel Milham, an epidemiologist in Washington state, sent a letter to the New England Journal of Medicine pointing out that electrical workers also had higher rates of leukemia. Many more papers on the occupational EMF–leukemia risk followed. Neither Palfreman nor Taubes mentioned them. (Taubes did cite male breast cancer as a possible risk.) Nor did the National Academy of Sciences report in 1996 —the one Park crowed about in the New York Times. When asked why not, one panel member replied it was not relevant to the assignment.

Brodeur may partly have been a victim of his own success. If EMFs were as bad as he was claiming, some asked, where are all the dead bodies? Brodeur had written about the dangers of asbestos as Selikoff spotlighted the association with mesothelioma. Very few challenged Brodeur. This cancer of the lining of the lungs became a “signal tumor” that made it far easier to identify asbestos victims. If asbestos had caused a more common type of cancer, it would have been much more difficult, for example, to attribute cases among members of the families of asbestos workers who had only been exposed to fibers brought home on clothing. Cancer is common, and a random tumor is often blamed on “bad luck.” After Selikoff, there was a direct line from mesothelioma back to the magic mineral.

Even with the advantage of a signal tumor, it took about 50 years to establish that asbestos caused mesothelioma. The first case of asbestosis was described in London in 1898, but the link to mesothelioma was not suggested until the 1940s and 50s and not widely accepted until 1960. No signal tumor has emerged for microwaves and EMFs. Without it, a cause-and-effect relationship is far harder to nail down —as is estimating the magnitude of the potential problem.

Cell Phones: Another Cover-Up

Brodeur never wrote about cell phones. They became a public health public issue in 1993, the year after he retired from the New Yorker. As attention shifted to microwaves, all the old loose ends came back into view. People were talking about the blood-brain barrier again. Swedish scientists were finding support for Frey. They too would be shut down.

How the cell phone cancer story played out over the next 30 years offers a textbook case study of what Brodeur was warning us about.

In 1993, a Florida businessman claimed on CNN that cell phone radiation had caused his wife to develop a brain tumor. All hell broke loose. The telecom industry promised $25 million for health studies and then didn’t do any serious research. The plan worked: it bought enough time for wireless technology to take hold. Convenience and utility won over public health. By the end of the decade, cell phone subscriptions had increased tenfold. Few now cared if there might be a problem.

Still, there were some lingering doubts: Everybody was or would soon be exposed to microwaves and no one knew what that might mean. FDA kicked the can down the road and asked the National Toxicology Program to study the cancer question. Meanwhile, epidemiological studies pointed to a cancer risk. By 2011, there was sufficient evidence for IARC to judge microwave radiation as a possible human carcinogen —much like it had with EMFs a decade earlier.

Seventeen years and $30 million after FDA’s request, the NTP announced the results of its study: Rats chronically exposed to cell phone radiation got cancer.

At a May 2016 press briefing, John Bucher, the head of the project, explained that the tumors the rats had developed —schwannomas— were the same type as those seen among heavy cell phone users (acoustic neuromas). “We felt it was important to get the word out,” he said.

Maggie Fox of NBC News asked why the NTP was fast-tracking the results before the final analysis had been completed. Bucher replied that they had far-reaching implications because they contradicted the thermal dogma that has been dominant for “many, many years.” The NTP wanted the public to know that microwaves can do more than heating.

No one wanted to hear the news. Here’s The Washington Post headline after the briefing:

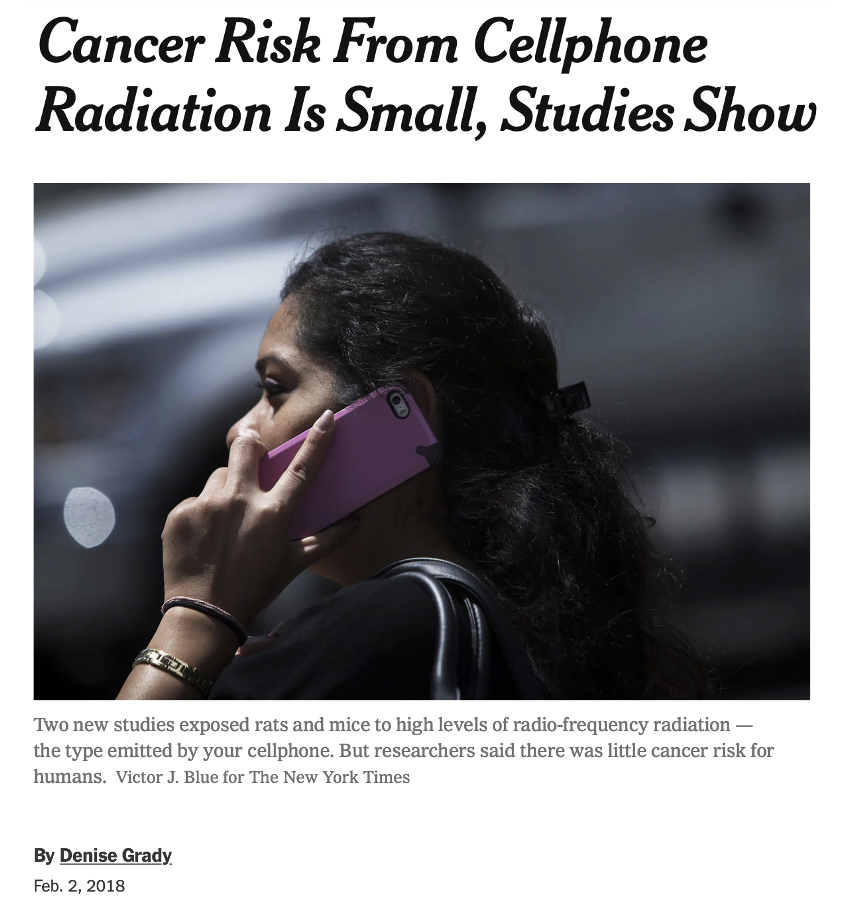

It took another two years for the NTP to prepare a final report. In the interim, there was a major rethink. The cancer findings were no longer seen as a public health imperative. When the NTP released a draft of the report in February 2018, Bucher pushed the new perspective. It worked —though admittedly it was not a hard sell. The headline in the New York Times the next day:

Gina Kolata, a senior Times science reporter, made a video to hammer the point home. There’s “overwhelming evidence” that cell phones do not lead to cancer, she said, “You can use a cell phone without worrying.”

The word on the street was that pressure to play down the NTP findings was coming from the very top. Apparently, Francis Collins, the director of the National Institutes of Health, was deeply skeptical and, it was said, his people were running interference, pointing reporters to objections made by one of his deputies at an internal NIH review.

Then something unexpected happened. There was one more review —this one by an outside group of pathologists and toxicologists. At a public meeting held on the NTP campus in North Carolina the following month, the panel insisted that the NTP had been right the first time around. They concluded that there was indeed “clear evidence” of cancer among the microwave-exposed rats. They couldn’t explain how and why microwaves could do this, but that’s what the data showed, and they were following the data.

Allan Frey had urged this approach 45 years earlier. Brodeur’s first New Yorker installment on microwaves in December 1976 closes with advice from Frey who, as Brodeur related, was “admonishing” his colleagues “about the narrowness and rigidity of their thinking and their approach to microwave research.”

Brodeur wrote:

“Frey urged his fellow-scientists to forget mathematical calculations that supposedly proved microwaves could not affect nerves and to recognize that very little was known about the workings of the nervous system, and even less about the possible interactions of radiofrequency energy with neural function.”

But they didn’t listen.

Final Report Leaked to New York Times

In November 2018, the NTP released its final report, which deferred to the advice of the external reviewers. There is clear evidence cell phone radiation causes cancer, was now the stated position of the U.S. NTP.

There was one last twist, however. The NTP may have succumbed to the external reviewers, but the NIH wanted to cover up the message. The final report was leaked to Broad —and only Broad. Everybody else, including me, got no more than a couple of hours advance notice of the formal release. Many major news outlets that had followed the story for years —the Wall Street Journal and the Associated Press, among them— were absent from the teleconference. There were only nine of us on the call. Two of the nine were from the New York Times: Broad and Ronnie Cohen, a health reporter.

Broad had the time to prepare. He even called me for some background a week or so before the press briefing —I have spoken to Broad irregularly for close to 40 years— but it was only later that I realized he was already on the story. Here’s his headline:

It’s a master class in distortion. Astonishingly, the Times downgraded the risk a full notch. Instead of clear evidence of cancer, the highest of five risk classifications, it was now some evidence. To add to the audacity, ‘some evidence’ was in quotes as if it were official.

There was also the gratuitous modifier “at least in male rats.” Broad and his editors on the science and health desks were implying that causing cancer in rats may be unrelated to the risk in humans. That logic turns modern toxicology upside down and begs the question, Why do an animal study in the first place?

FDA No Longer Believes in Animal Studies

The FDA, which had originally asked for the NTP study, now repudiated it. “We must remember the study was not designed to test the safety of cell phone use in humans, so we cannot draw conclusions about the risks of cell phone use from it,” the agency said in a press statement.

The link to cancer continued to get stronger. During that same spring of 2018, the Ramazzini Institute in Bologna announced that it too was seeing more schwannomas in rats in its own long-term microwave exposure study. “That’s more than a coincidence,” one close observer told me at the time. Could this be a sign that schwannoma is a signal tumor following microwave exposure? No one seemed interested in finding out.

Current health standards remain “acceptable for protecting public health,” the FDA declared. The agency appeared to ignore that, as Bucher had pointed out at the first press conference, those standards were based on the heat-only assumption which was no longer viable.

Two years ago, Linda Birnbaum, who, as the director of the NTP, shepherded the cell phone study through its various peer reviews, predicted that, based on the NTP and Ramazzini schwannoma findings, IARC would soon upgrade the microwave risk at least to probable carcinogen —and perhaps to a known one.

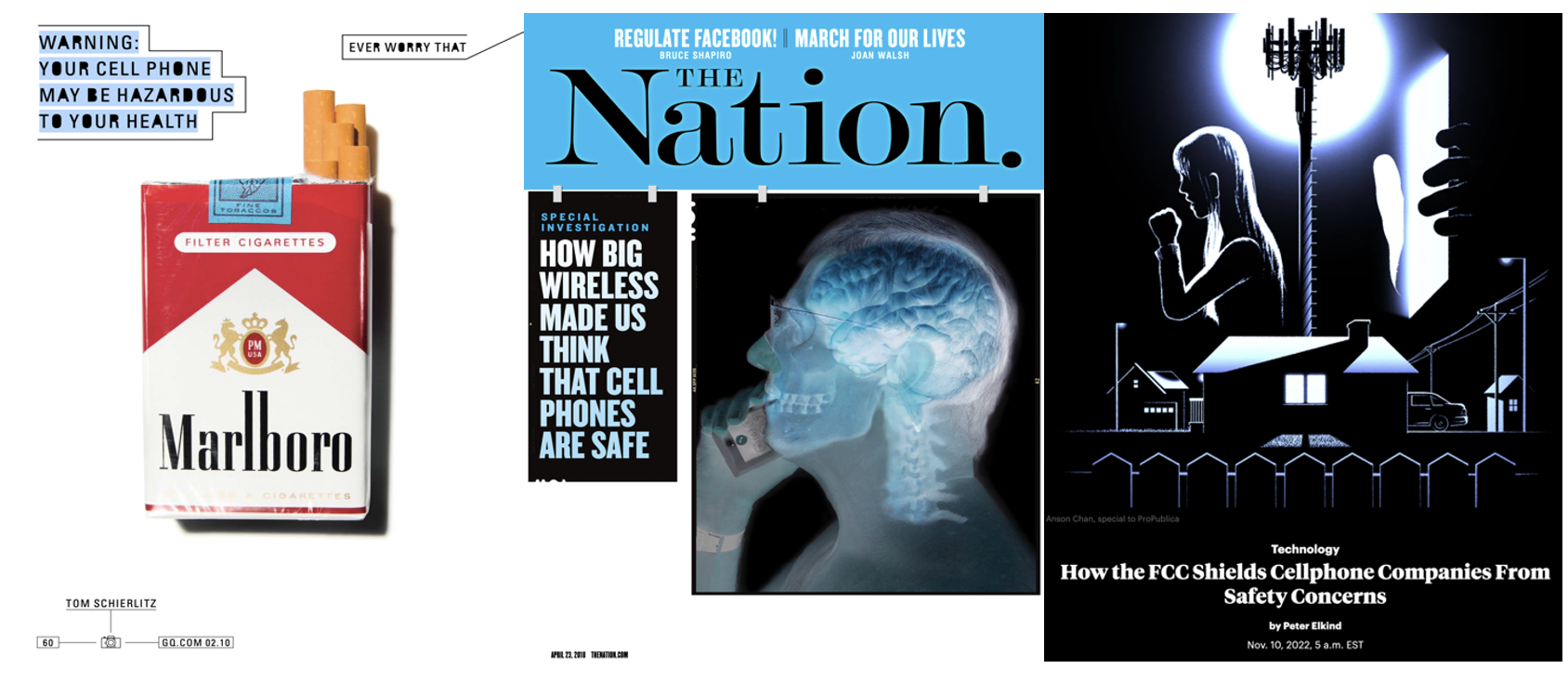

Cell Phone Features in GQ, The Nation and ProPublica

Cell Phone Features in GQ, The Nation and ProPublica

The cell phone story goes on, if only because so many paths have led to cancer. Every few years, it gets re-discovered by reporters who are following Brodeur’s trail. There have been major pieces in GQ (2010), The Nation (2018), The New Republic (2020) and ProPublica (2022). But concerns soon passed —with so little research going on, there’s not much new to write about.

All the while, Broad continues to bash the issue and use Brodeur as a foil. In a 2019 Times story headlined, “The 5G Health Hazard That Isn’t,” Broad cited him twice —as well as both Zapping and Currents— as partly responsible for the furor over the latest cell phone technology.

This was another Broad hit job, based on his own fabrications. The target was David Carpenter, a public health physician in Albany and the nation’s most important advocate for caution on cell phone radiation. Carpenter was also the one, who, in the early 1980s, did not allow the Wertheimer power-line study to be ignored and commissioned the Savitz replication project.

A few months later, Broad was back, this time with a page-one story all but accusing Carpenter of being a Russian agent of disinformation.

In the 20 years the NTP took to complete the study, the potential economic fallout of a cancer verdict had mushroomed. It wasn’t about just cell phones anymore, but all of wireless. If the radiation could cause cancer, it would affect more than the military and communications companies. The American and world economies would be at risk. The CTIA, a trade group, has estimated that the wireless industry contributed nearly $5.4 trillion to the U.S. GDP over the last decade. People now use their smartphones as mobile computers rather than as telephones. How would everyone react if there was no more Wi-Fi, or no more cloud to access everything, everywhere?

5G promised to be so pervasive that the New York Times opened a “5G Journalism Lab” in partnership with Verizon, the wireless giant. This obvious conflict of interest was never disclosed by Broad’s editors and superiors. They simply covered it up.

Does It Matter?

If there are effects —which is really hard to deny— the questions become: How important might they be? and, How would we know if we’re being affected? We are all exposed all the time, so there’s no comparison group anymore. We’re all in this together! The effect would have to be very large to be detected. A signal tumor or the like would be helpful, but even that would take a lot of work. As for isolating any more subtle adverse effects, good luck with that.

There is, however, one subtle electromagnetic effect that everybody agrees is real: the avian compass. It’s extraordinary: Birds can fly to a pinpoint location thousands of miles using clues from the Earth’s magnetic field. Once dismissed, it’s now part of the scientific canon.

A German group in Oldenburg has been studying the avian compass in European robins for years, and they were stunned to discover that their robins lost their sense of direction when exposed to electromagnetic noise common in most cities. Writing in Nature in 2014, they called the effect “remarkable” because it showed the birds were sensitive to “exceedingly weak” man-made magnetic fields. Later, in a Scientific American article titled, “How Migrating Birds Use Quantum Effects to Navigate,” they described the fields as “astonishingly weak.”

Covers of Nature (June 24, 2021) and Scientific American (April 2022)

In a comment accompanying the 2014 Nature paper, Joseph Kirschvink, a geo-biophysicist at CalTech, explained the implications for the long-simmering health controversy:

“The levels of radiofrequency radiation that affected the birds’ orientation are substantially below anything previously thought to be biophysically plausible and far below levels recognized as affecting health.”

One of the German researchers told a reporter that he could turn the effect on and off as easily as “flipping a switch.” Yet, it took them years to work out that it was the ambient electromagnetic noise that was confusing the birds.

It’s not just birds that are sensitive to weak radiation, so are many mammals, reptiles and insects. Could humans be too? Surely it’s hubris to assume otherwise. We are mammals who evolved in an electromagnetic environment. Why should anyone be surprised that we might be affected by changes?

Paul Brodeur gave us warnings that many rejected. It’s not too late to listen. With enough effort, we could harness the good effects and avoid the bad ones. But the first small step is to acknowledge that non-ionizing radiation is biologically active —even if we don’t know exactly how.

Keep in mind that we still don’t know how asbestos causes mesothelioma.

“They Lied”

One last anecdote: Of all the conversations I had with Brodeur over the years, this one stands out most in my mind. It was in 2011 and was about a dispute he was having with the New York Public Library. In an email Brodeur called it his “latest crusade.”

A few years before he retired from the New Yorker, Brodeur donated some 300 boxes of his papers to the NYPL. They were processed, catalogued and stored and, in 1998, he was told that they were part of the permanent collections. Then, a dozen years later —18 years after his original gift— Brodeur received a letter from the NYPL informing him that a “substantial quantity” of his papers would be returned to him or otherwise disposed of. They would not have a permanent home in the Library.

Brodeur was furious and demanded that the NYPL return all his papers. It refused. Brodeur went public and asked his friends and colleagues to write letters of support to Paul LeClerc, the Library’s CEO. He asked me, and I too wrote to LeClerc. But before I did, I asked Brodeur whether he was sure he wanted to take everything away from the Library. The NYPL, I told him, is a great institution and by far my favorite in New York. Maybe some of your papers do belong there, I said.

“Louis,” he replied, “I have no choice. They lied.”

All the Brodeur papers are now in the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University.

______________________