Yuri Grigoriev, Russian Biophysicist

And Non-Thermalist, Dies at 95

Stressed the Importance of Modulations and Strict Standards

Founder of Russian National Committee on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection

Yuri Grigoriev (1925-2021) with his Soviet State Prize medal

Yuri Grigoriev, a Russian biophysicist and a singular figure in the world of electromagnetic health and safety over the last 50 years, died in Moscow on April 6 at the age of 95.

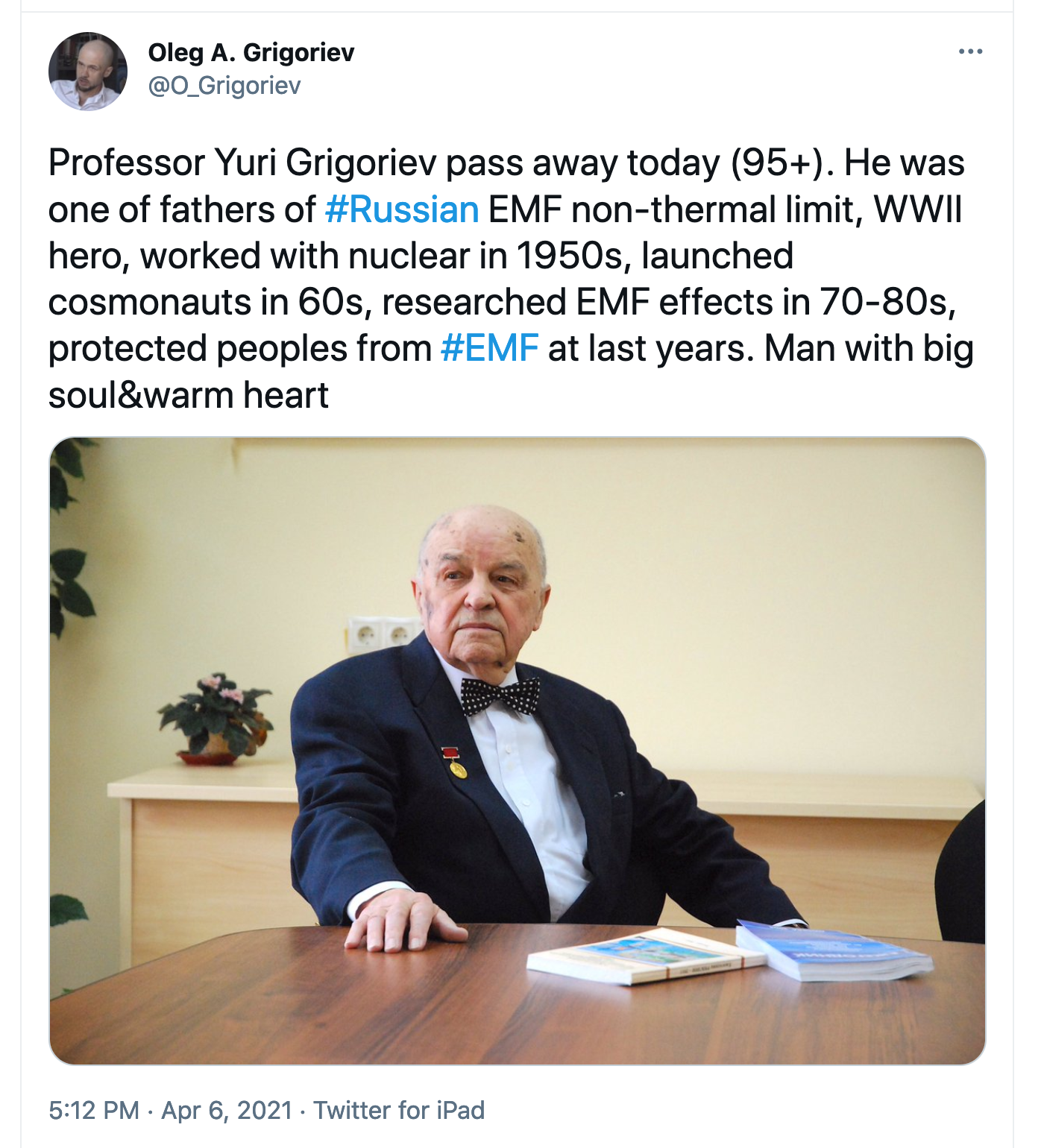

“We have lost a ‘scientific grandfather’,” Oleg Grigoriev told Microwave News. “Yuri supported scientists and pushed them to do research. He was greatly respected by all his colleagues, myself included.” Yuri was one of Oleg’s mentors —they are not related— encouraging him to finish his doctoral dissertation. Oleg later served as the director of the Center for Electromagnetic Safety in Moscow for 20 years, until 2015.

Yuri was a man with a “big soul and warm heart,” Oleg Grigoriev wrote on Twitter.

In contrast to many of his counterparts in the West, Yuri Grigoriev promoted the idea that microwave biology is more complex than simple tissue heating. His views were based, in part, on his own research showing the importance of modulation characteristics.

He is also known for his steadfast support for the Soviet and later Russian health standards, which are designed to protect against long-term effects and are much stricter than those adopted in most other countries. ANSI, ICNIRP and the IEEE have never acknowledged the existence of chronic effects, setting their exposure limits at levels that are up to a thousand times higher.

The contrasting view of what the standards should be has been a source of East-West tension since the Cold War began. It continues today.

“Professor Grigoriev was one of the first scientists to draw conclusions on the role of modulation in RF biological effects and on the increased sensitivity of children to RF,” said Igor Belyaev, the head of the Department of Radiobiology at the Biomedical Research Center of the Slovak Academy of Sciences in Bratislava.1

Grigoriev was popular and had many friends on both sides of the aisle —whether or not they shared a common outlook. “His great heart, generosity and friendly smile will be sorely missed,” Michael Repacholi, the founder and former chairman of ICNIRP, told me.

With Michael Repacholi in Moscow in 1999

With RRT’s Eileen O’Connor and Cindy Sage (co-editor of BioInitiative Report) in London in 2008

With RRT’s Eileen O’Connor and Cindy Sage (co-editor of BioInitiative Report) in London in 2008

“Yuri was a real hero,” said Eileen O’Connor of the Radiation Research Trust, a U.K. citizens’ advocacy group. “He was a great scientist with strong moral and ethical principles.”

“It is so sad to know that my old dear friend Yuri passed away,” wrote C.K. Chou, formerly with Motorola, in an email message to colleagues. “I already miss him.” Chou first met Grigoriev in Seattle in the early 1980s, when he was a graduate student in Bill Guy’s lab at the University of Washington. Chou has played a leading role in the writing of RF exposure standards for decades, often disagreeing with Grigoriev on how they should be set.

A Life of Ups and Downs

Grigoriev was born in Ukraine in 1925; his family moved to Moscow when he was seven years old. He gained entry to medical school in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg) in 1944, but only after serving at a field hospital on the front lines in WWII —where he contracted typhoid fever.

The highs and lows would continue. But whatever the setback, Grigoriev regrouped and moved forward. He was a survivor.

Grigoriev became a radiation biologist, earning a doctorate in 1953. One of his first assignments was at the Institute of Biophysics in Moscow, investigating the effects of ionizing radiation in medical applications (for instance, in radiotherapy). A later project was on how to protect cosmonauts from the high-energy cosmic rays encountered in space travel.

He did well. He won the Order of Lenin in 1976 and the prestigious State Prize in 1978. His success offered him the coveted opportunity to travel outside the Soviet Union. Grigoriev took good advantage; he came to the U.S. often, and he got around —to Berkeley, the Houston space center, even the White House.

Grigoriev’s expertise on ionizing radiation would later take him to Chernobyl a few weeks after the reactor meltdown in 1986 to help care for the workers. “We landed in Kiev, got into a helicopter and flew to hell, in the truest sense of the word,” he later recalled.

In April 1977, Grigoriev was appointed the head of a new research lab at the Institute of Biophysics in Moscow for the study of the biological effects of low- and high-frequency radiation. At the same time, he became the deputy director of the entire Institute.

But then, a decade later, he fell out of favor with the KGB and was forced out of the radiation program and the Institute. Nevertheless, Grigoriev managed to hang on. He stayed active and continued to do research, confer over standards and travel widely.

In 1997, five years after Repacholi set up ICNIRP, Grigoriev founded a Russian version, albeit with a different structure but with a very similar name: the Russian National Committee on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection (RNCNIRP). He was the first chairman.

His life took another turn in 2014. Grigoriev, now 88 years old, was asked to step down from the RNCNIRP chair. Some believed he had overstepped, and it was time for change. Oleg Grigoriev, the head of the non-ionizing laboratory at the Institute of Biophysics, became the new chairman.

With Oleg Grigoriev in Moscow in 2015

Yuri Grigoriev remained busy to the end. But his reach was now limited, and age was forcing him to slow down. He had lost his platform; still, he kept in touch with campaigners around the world. They welcomed his non-thermal outlook and his advocacy of precaution. Several told me that they started worrying about him at the end of last year when his Christmas card never arrived.

An Accidental Discovery

Grigoriev’s segue from the ionizing to the non-ionizing side of the electromagnetic (EM) spectrum happened by chance. In the 1950s, he was a member of a research group studying the effects of X-rays on the electrical activity in the brains of rabbits. To their surprise, they observed some dramatic changes in the EEGs of the controls —that is, when the X-ray source was turned off. They became convinced that a nearby transformer was responsible and that EMFs could have a “direct action” on the brain. These findings were reported in the Bulletin of Experimental Biology and Medicine in 1960. It was the first of Grigoriev’s many papers on EM radiation.

Allan Frey, an American biophysicist who has made a number of original contributions to EM science —most notably for discovering microwave hearing, often called the Frey effect— met Grigoriev during a month-long trip to the Soviet Union in the early 1970s.

The Soviet Academy of Sciences had invited Frey to give a series of seminars. One stop on the itinerary was the Academy’s Institute of Biophysics in Pushchino, a so-called science city located about 60 miles south of Moscow. Grigoriev came down to meet Frey and hear what he had to say.

At a formal dinner that night, Frey was seated between Grigoriev and Inal Akoev, the institute’s deputy director. “Grigoriev served as my host and was very friendly,” Frey told me recently. “He was very interested in what I was finding about the importance of carrier frequency and modulation.”

Frey, Grigoriev and Akoev shared a common interest in how modulating a carrier wave can change its biological impact. Modulation is a way to alter the otherwise simple sine waves of the carrier signal to accomplish a given goal. Amplitude modulation, for example, gives you AM radio. You tune in to a specific frequency for a favorite station, but it’s the modulation of that carrier frequency which brings the words and music.

The Frey effect is, after all, about modulation —pulse modulation, as used in radar. People can hear microwaves only when they are pulsed. As Frey explained when he presented microwave hearing as a “new phenomenon” in 1962, whether you hear a “buzz, clicking, hiss or knocking” sound depends on the pulse modulation.

A.H. Frey, Journal of Applied Physiology, 1962

A.H. Frey, Journal of Applied Physiology, 1962

Grigoriev and Frey stayed in touch for years afterwards.

At the time, Pushchino was a major center for research on EM bioeffects. “I was told I was the first Westerner allowed into Pushchino,” Frey recalled. “Some U.S. agencies were most interested in talking with me about the place when I got back.”

Modulations — Studied and Ignored

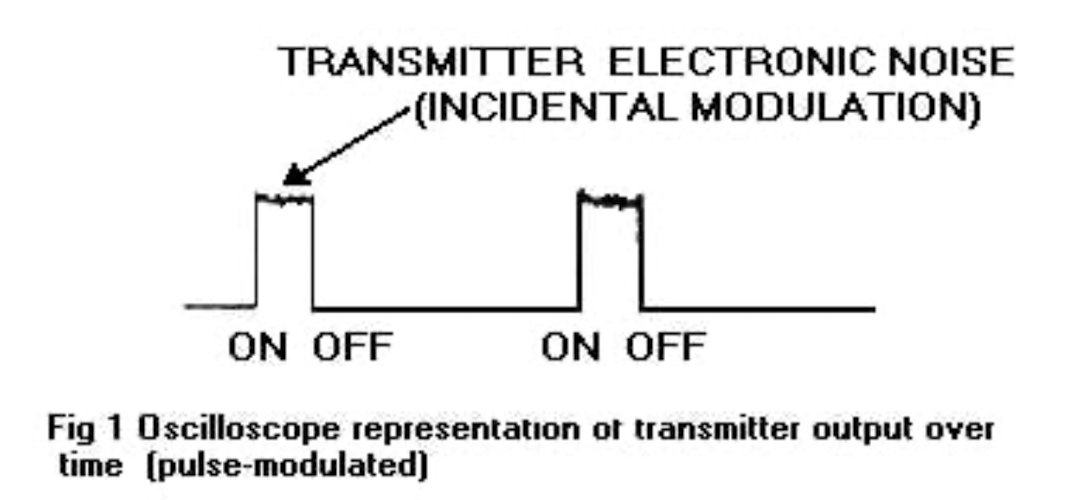

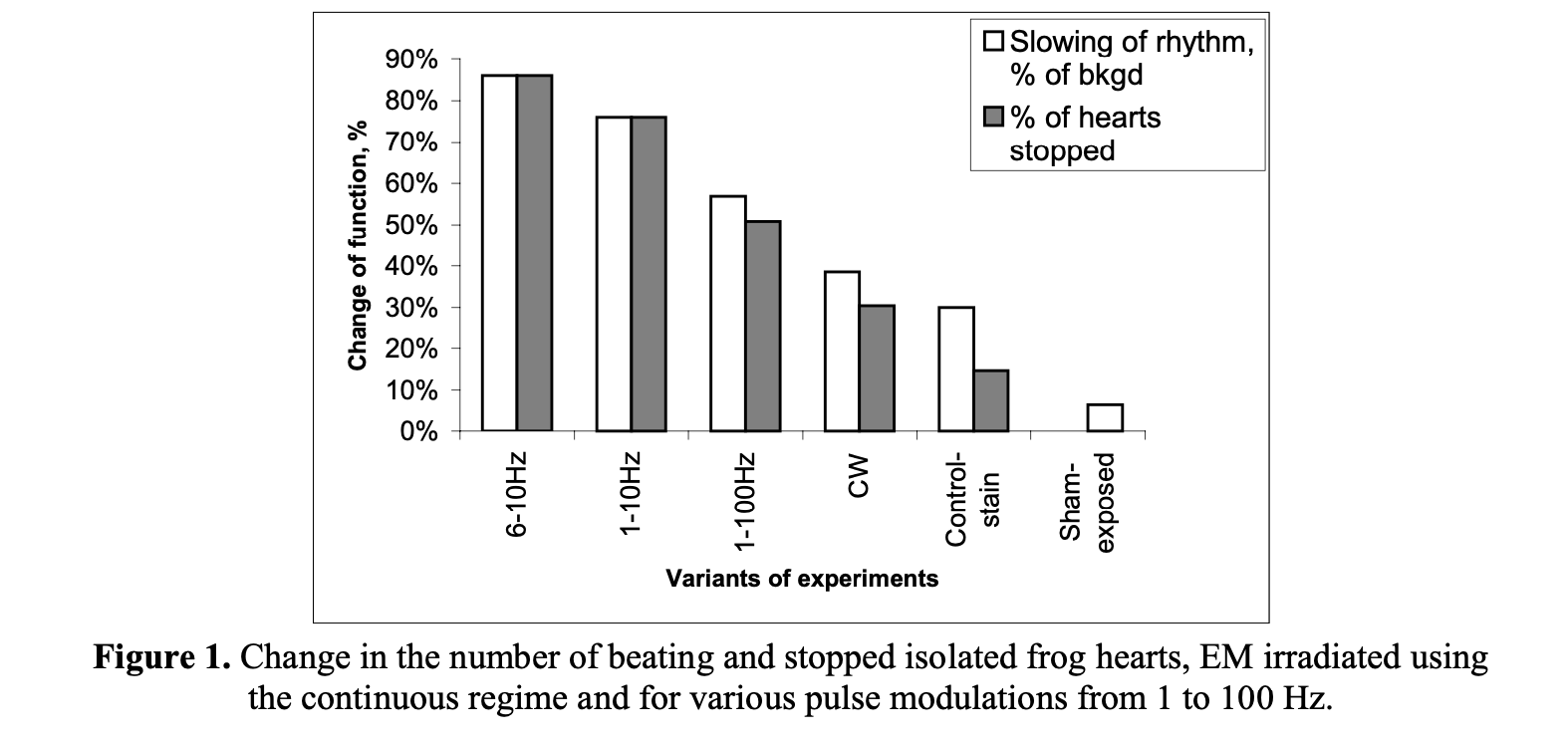

One of Grigoriev’s best-known experiments was a variation on an early Frey study. In 1968, Frey showed that pulsed radiation affected the beating heart of a frog. Grigoriev ran a similar study in the 1970s, using 9.3 GHz with low frequency (<10 Hz) amplitude modulation, rather than pulsed modulation. Grigoriev saw a much larger effect with the AM than with simple unmodulated sine waves (see below; his study was not published until the 1990s).

Y.G. Grigoriev, “Basic Materials for Electromagnetic Field Standards,” November 2003, p.67

Y.G. Grigoriev, “Basic Materials for Electromagnetic Field Standards,” November 2003, p.67

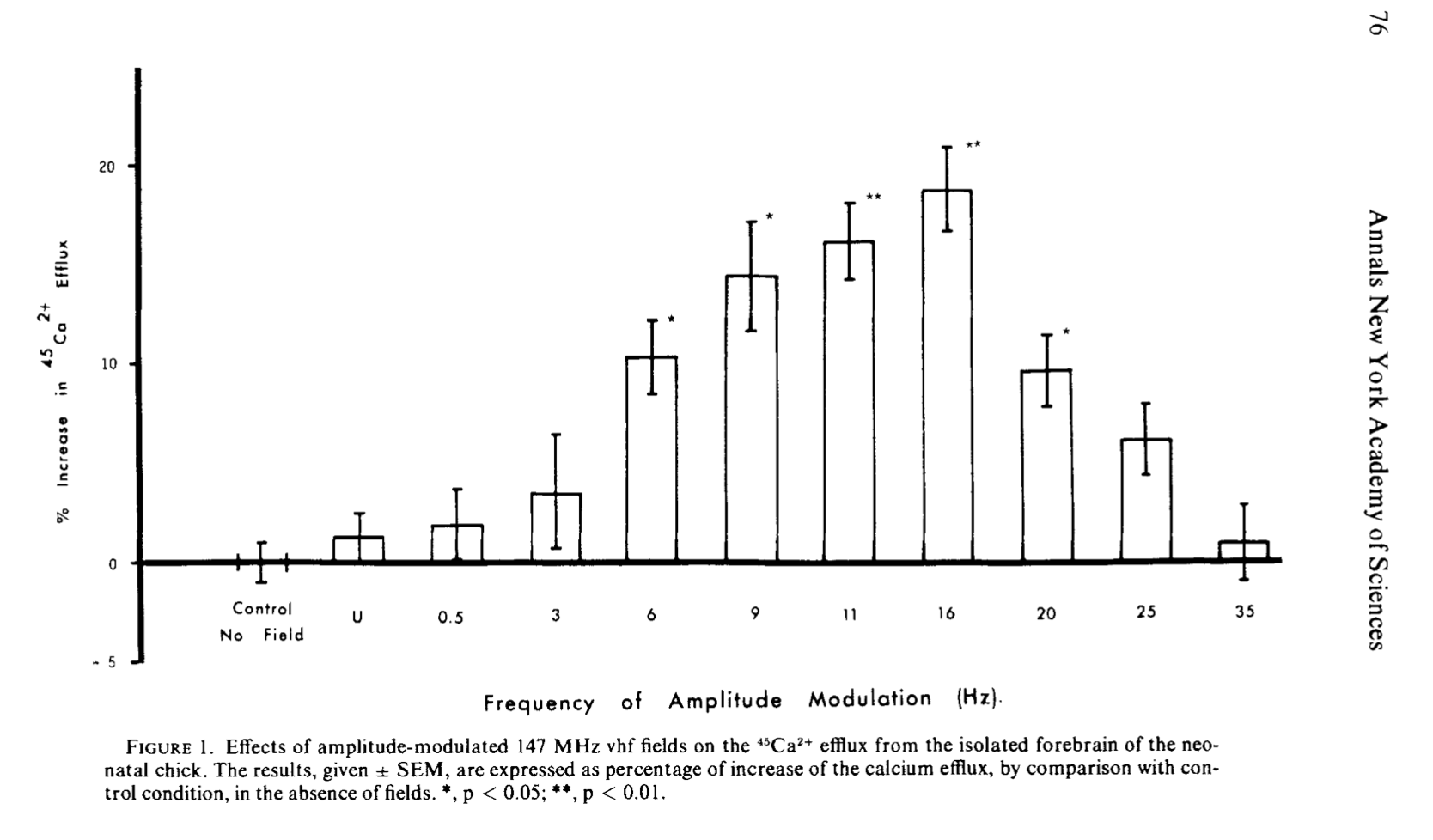

At about the same time that Frey was visiting Pushchino, Ross Adey and Suzanne Bawin at the UCLA Brain Research Institute in Los Angeles were seeing a similar “window,” as they called it, in how the radiation affected the movement of calcium ions through cell membranes. They found a maximum effect with 16 Hz AM (see below). This work was later replicated by Carl Blackman at an EPA lab in North Carolina.

S. Bawin, L. Kaczmarek and W.R. Adey, Annals of the NYAS, 1975

S. Bawin, L. Kaczmarek and W.R. Adey, Annals of the NYAS, 1975

In a major review of the literature in 1981 —it’s been cited more than 1,000 times in subsequent papers— Adey highlighted the importance of modulation:

“[T]here is unequivocal experimental evidence that fields from [10 Hz – 450 MHz] interact directly with brain tissue. A striking feature of some of these observed interactions with weak RF fields is their relationship to modulation in the ELF range and not to the radio carrier frequency.”

This finding has largely been discounted by those setting exposure standards in the U.S and by ICNIRP.2 Even if it’s a true biological effect, the rationale goes, it doesn’t necessarily mean there’s a health effect. The subtext is that if modulations were to be taken into account it would imply the existence of non-thermal effects, and that would be unacceptable.

Grigoriev’s work with frog hearts fared no better. Even worse, it was ignored. As he lamented in a 2003 review, “Unfortunately, the results of the examinations conducted in Russia on a biological effect of modulated EMF till now are not known in the West and in the USA.”3

Still, Grigoriev didn’t let up the pressure. In a joint 2007 paper, he and Igor Belyaev made a plea:

“The findings regarding the role of modulation are extremely important to consider in non-thermal microwave exposures and should be more thoroughly studied using those specific types of modulations that are used in mobile communications.”

Advocate for Strong Exposure Limits

Grigoriev probably had the most impact as the standard-bearer for the Russian exposure limits. These have always been much more strict —at one point,10,000 times stricter— than those in the U.S. and most Western countries (Switzerland and Italy are two exceptions).

The disconnect between the two sets of standards has been a source of U.S.-USSR/Russian discord for 50 years. ‘What do they know that we don’t which makes their standard so much stricter than ours?’ was what every journalist asked when approaching this story. There were no good answers, and suspicions about safety grew.

As Don McRee of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) wrote in 1979: The “large volume of Soviet and East European research has been a driving force in the United States in producing concern over the biological effects of microwave radiation.”

The U.S. military was ready to do whatever was necessary to make sure that a Russian-style standard was never adopted in the West. If that were to happen, planners worried, it would limit the use of many military systems, most especially radars, as well as leave the services liable to compensation claims from injured workers.

The late Herbert Pollack, a medical doctor who worked for the state department on microwave health issues and who was heavily involved in the Moscow embassy affair, explained what was at stake at a Senate hearing [p.279] in 1977:

“[I]t can be said that the Soviet military are not bound by their current safety standards, but the U.S. military are bound by ours. This is important to bear in mind if new standards are promulgated. It is difficult to imagine that the Soviet military could function effectively under the restrictive natures of their current limits.”

Pollack did not say so directly, but the implication was evident: If a Soviet-style standard4 were adopted in the U.S.,5 the military would be unable to function effectively.

The so-called flaws of the Soviet standard became a pervasive American meme. Here’s how NIEHS’ McRee put it:

“First, the [Soviet] maximum permissible exposure level is set at the value where no biological effects occur. No differentiation between effects and hazards is made in setting their standards.”

The message was that not only was the standard unnecessarily strict, but the research it was based on was so sloppy and ill-defined that it was next to impossible to repeat. As McRee wrote:

“Most of their papers do not give details concerning the experimental design and exposure techniques. Because of these unknowns, a strong motivation to ignore much of the Soviet and Eastern European results exists in the U.S.”

A joint U.S.–Soviet microwave program was set up in 1975 to see if the scientists could resolve their differences. McRee led the U.S. delegation. They didn’t make much progress. Part of the reason was the scarcity of money for research in the U.S.

But there was another factor too: One of the first American experiments to see if a Russian experiment could be repeated —carried out by Richard Lovely at the University of Washington in Seattle— supported the Soviet findings.6 After that, the U.S. replication efforts lost their urgency and faded away.

U.S. and Soviet scientists meet in Kiev in 1977; McRee is third from right; full cast below7

In an email exchange for this article, I asked Frey about attitudes to the Soviet research in the U.S. at that time. “The Soviets did some fine work,” he replied. “I saw a lot of it in the Soviet Union. It was grossly misreported and misrepresented in the U.S.”

Soviet Microwave Standard Revised in 1984

The individual most responsible for Soviet microwave standards was Michael Shandala, the director of the Marzejev Institute of Public Health in Kiev (now Kyiv). He released a revised limit of 10 μW/cm2 in 1984. It was double the previous one, but still up to 500 times stricter than the American standard (details: MWN, June 1985).

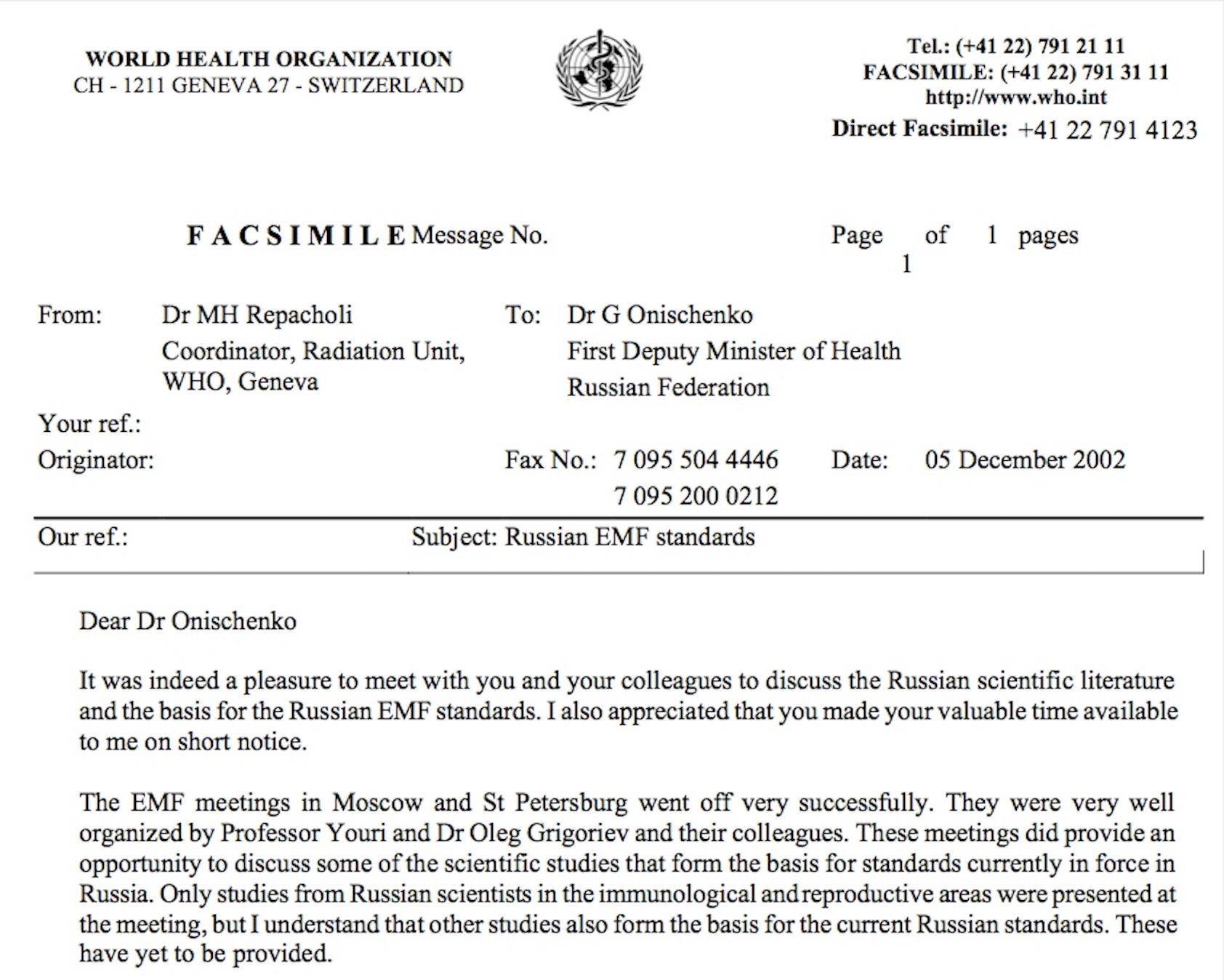

Nothing much changed for years —until cell phones came on the scene. Then, a new effort was made to bridge the gap between the East and West. It was called harmonization and became the mission of Michael Repacholi at the WHO International EMF Project in Geneva with the financial support of cell phone manufacturers and network operators.

Harmonization meetings were organized. The first was held in Moscow in 1998, another the following year. Grigoriev could see no progress. “So far we have entirely different approaches to harmonization,” he said at the 1999 conference (see MWN, N/D99).

At the next meeting, in 2002, Grigoriev had not budged. “Currently, our knowledge on the health effect mechanism of RF EMF of low-intensity confirm the justified strict-acting standards imposed in Russia,” he stated.

In a separate paper, he called for addressing the “unsolved problem” of the role of EMF modulation in the development of bioeffects.

At the time of the 2002 meeting, Repacholi went over both Yuri and Oleg Grigoriev’s heads. He made the case for harmonization in a meeting with the First Deputy Minister of Health, Gennady Onischenko (see below). Nothing came of this either.

Excerpt of fax from WHO’s M. Repacholi to G. Onischenko, December 5, 2002

Excerpt of fax from WHO’s M. Repacholi to G. Onischenko, December 5, 2002

Repacholi didn’t give up. With the support of the GSMA, the association of cell phone network operators, he organized another meeting in 2012. Once again, little progress was made.

The chasm between the Russian and American/ICNIRP limits remains today.

A Last Hurrah

Grigoriev is gone, but he is having one final act.

During his last years, Grigoriev became more and more of an activist, calling for the application of the precautionary principle, especially when children could be exposed to electromagnetic radiation. “Man has conquered the Black Plague,” he would say, “but he has created new problems —EMF pollution.” He called the proliferation of RF sources “out of control.”

Before he died, Grigoriev finished a book detailing the challenges posed by the introduction of 5G networks, written with coauthor A.S. Samoylov, a specialist in sports medicine.

Leonid Ilyin, the former director of the Institute of Biophysics in Moscow, set out their concerns in a preface to the book: “The entire world’s population will be trapped for life in the electromagnetic grid of millimeter waves and no one will be able to avoid their impact.” Ilyin, now 94 years old, is a “Hero of Socialist Labor,” one of the country’s highest honors.

Grigoriev’s Final Work: A Book on the Dangers of 5G

Grigoriev’s Final Work: A Book on the Dangers of 5G

A last photo of Yuri Grigoriev, made available to Microwave News by Oleg Grigoriev, shows him in an embroidered coat, a gift from colleagues in Uzbekistan.

June 14, 2021

5G Book: Free Download

A full copy of Grigoriev’s last book —5G Cellular Standards— is now available online at no cost. The text is in Russian, except for the preface by Leonid Ilyin, which is in English. The 196-page pdf is available here. Unfortunately, there are no page numbers.

Joel Moskowitz has posted some additional details on his website, Electromagnetic Radiation Safety.

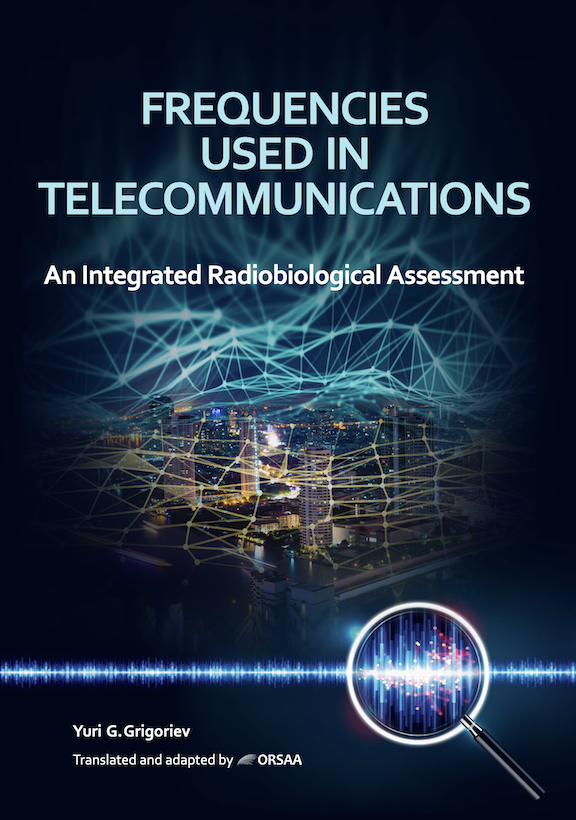

English Translation Now Available

April 9, 2022

The Oceania Radiofrequency Scientific Advisory Association (ORSAA), based outside Brisbane, Australia, has published an English translation of Grigoriev’s 5G book, under the title, Frequencies Used in Telecommunications: An Integrated Radiobiological Assessment.

The book, which runs 198 pages with 369 references (many with links), is a free download.

_________________________

FOOTNOTES

1. Belyaev made these comments to David Wedege Petersen, a Danish journalist, for his own obituary of Grigoriev on his “Lost Thread” website.

2. The telecom industry and the military have long maintained that modulation is not important when it comes to health effects and therefore exposure standards. For one example, see these comments from Ross Adey in 2001 on a cell phone industry workshop that sought to dismiss the idea that modulation might need to be taken more seriously. According to Livio Giuliani, the former director of research at Italy’s National Institute for Prevention and Occupational Safety (ISPESL, now INAIL), there was a proposal in the late 1990s to include AM in a update of the Italian exposure limits. For AM radiation, the limit would be reduced by half: 3 V/m instead of 6 V/m. It was not approved.

3. Grigoriev noted one exception: a 2000 review by Andrei Pakhomov and Michael Murphy, who were both working for the U.S. military at the time. Pakhomov, who was trained in Russia, is now with Old Dominion University in Virginia. He declined to be interviewed for this article. The U.S. Air Force had good reasons to be interested in AM signals. The radiation from the PAVE PAWS system, one of its most powerful radars, operating at 420-450 MHz, is AM at 18.5 Hz, according to a 1979 engineering report by the National Research Council of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences. To Adey’s everlasting rage, the Air Force never acknowledged that AM made the radiation any different from CW.

4. Soviet military standards for EM radiation were different than those for workers and the public until 1999, according to Oleg Grigoriev. Indeed, the military limits were closer to, though not the same as, the U.S. military’s limits.

5. In the 1950s, a number of U.S. electronics manufacturers (e.g. AT&T) set their own internal safety limits that were closer to the Soviet limits than those of the U.S. military. The companies were soon brought in line by the U.S. Air Force and what was commonly known as the 10 milliwatt standard (more precisely, 10 mW/cm2) took hold. It was a simple thermal limit, and it came with a duty to deny the existence of any and all non-thermal effects —as well as to disparage the Soviet limits as being scientifically unsupportable.

6. Here is part of what McRee wrote in 1980:

“It was then decided to perform a duplicate experiment in order to determine if similar effects could be observed. … Dr. Richard Lovely of the University of Washington, project leader on the duplicate project, spent 4 weeks in the Soviet Union to observe the behavioral and biochemical tests being performed on the animals. The results of these duplicate investigations are very interesting. The U.S. study found a drop in sulfhydryl activity and blood cholinesterase as was reported in the Soviet study. .... In addition all behavioral parameters assessed at the end of 3-month exposures revealed significant differences between groups in the same direction as those reported in the Soviet study ... This replication of the Soviet results at 500 μW/cm2 emphasizes the need for performing long-term low-level microwave bioeffects research by U.S. investigators and the necessity of evaluating seriously the results of Soviet and Eastern European research before it is considered invalid. These experiments should also be replicated by independent investigators in the U.S. since the health implications of the above effects could be serious.”

There was no follow-up.

7. On the far left is believed to be Yuri Zubarev, the Soviet deputy minister of communications; the others are all American. From left to right: William Kaune (Battelle Pacific NW Lab), A.W. (Bill) Guy (University of Washington, Seattle), Don McRee (NIEHS), Joe Elder (EPA); and Richard Phillips (Battelle Pacific NW Lab). The picture was taken at the Marzejev Institute of Public Health in Kiev/Kyiv in 1977. Twenty years later, three of the Americans (Elder, Guy and McRee) were working for the cell phone industry.